6 Unsupervised classification

The objective of unsupervised classification is to determine the \(K\) classes \(\mathcal{P}_{K} = {C_1,··· ,C_K}\) of the n individuals of X such that a class is a grouping of individuals :

similar to each other (homogeneity in the class)

different from individuals in other classes (well-separated classes)

How to automatically define groups of individuals or variables that are similar ?

There are many automatic clustering algorithms that are distinguished by :

the nature of the objects to be clustered : individuals or variables

the nature of the data : quantitative, qualitative or mixed

the nature of the classification structure : partition or hierarchy

the nature of the approach used : geometric approach (distance, dissimilarity, similarity) or probabilistic approach (mixture models)

Here, we are interested in the classification of individuals described by quantitative data, using geometric approaches using distances.

We have a set of points of \(R_p\) (data) for which we do not know the labels, but that we want to group together in an “intelligent” way.

| X1 | X2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Brigitte | 140 | 6.0 |

| Marie | 85 | 5.9 |

| Vincent | 135 | 6.1 |

| Alex | 145 | 5.8 |

| Manue | 130 | 5.4 |

| Fred | 145 | 5.0 |

6.1 Partition

A partition \(\mathcal{P}\) into \(K\) classes of individuals is a set of non-empty classes, two by two disjoint and whose union is the set of individuals:

\[\begin{align*} C_k &\ne \emptyset, \quad \forall k \in \{1, \dots, K\} \\ C_k \cap C_{k'} &= \emptyset, \quad \forall k, k' \in \{1, \dots, K\} \\ C_1 \cup \cdots \cup C_K &= \Omega \end{align*}\]For the example \(\Omega = \{Brigitte, Marie, Vincent, Alex, Manue, Fred\}\), I proposed a partition \(\mathcal{P}^3 = \{C1,C2,C3\}\) into 3 classes of the 6 individuals below.

\(C1 = \{Marie, Brigitte\}\)

\(C2 = \{Alex, Vincent\}\)

\(C3 = \{Manue, Fred\}\)

6.2 Hierachy

A hierarchy H of a set of parts \(\mathcal{X} = \{x_1,...,x_n\}\) satisfying:

\(\forall i \in [1,n], \{x_i\} \in H\)

\(\mathcal{X} \in \mathcal{H}\)

\(\forall A, B \in \mathcal{H}, A \cap B = \emptyset \: or A \subset B \: or B \subset A\)

A dendrogram (or hierarchical tree) is the graphical representation of an indexed hierarchy and the function h measures the height of the classes in this dendrogram.

\(\mathcal{H} = \{ \{Brigitte\}, \{Marie\}, \{Vincent\}, \{Alex\}, \{Manue\}, \{Fred\},\)

\(\{Alex,Fred\},\{Brigitte,Vincent\},\{Brigitte,Vincent,Manue\},\)

\(\{Brigitte, Marie, Vincent, Alex, Manue, Fred\} \}\)

By defining a cut level, we will obtain a partition.

\(\mathcal{P} = \{ \{Marie\},\{Alex,Fred\}, \{Manue\}, \{Brigitte\} ,\{Vincent\} \}\)

\(\mathcal{P} = \{ \{Marie\},\{Alex,Fred\}, \{Manue\}, \{Brigitte,Vincent\} \}\)

\(\mathcal{P} = \{ \{Marie\},\{Alex,Fred\}, \{Manue,Brigitte,Vincent\} \}\)

\(\mathcal{P} = \{ \{Marie, Alex,Fred\}, \{Manue,Brigitte,Vincent\} \}\)

Dendrogram

6.3 How to measure the distance between individuals ?

Clustering methods require the ability to quantify the dissimilarity between the observations.

6.3.1 Binary data

For binary data (i.e. vectors composed of 0 and 1), we construct the cross-table between two individuals \(i\) and \(i′\) :

\(I_1\) = {1,0,0,1,1,1,0,0}

\(I_2\) = {0,1,0,1,1,1,1,0}

| 1 | 0 | individual i’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| individual i | 1 | a | b | |

| 0 | c | d |

There are then several normalized similarity indices (\(s_{max} = 1\)):

Jaccard \(\frac{a}{a+b+c}\)

Russel and Rao \(\frac{a}{2a+b+c+d}\)

Dice or Czekanowski \(\frac{2a}{2a+b+c}\)

Ochiai \(\frac{a}{\sqrt{a+b} + \sqrt{a+c}}\)

A dissimilarity index:

\[ d(i,i') = s_{max} - s(i,i') \]

6.3.2 Quantitative data

For quantitative data x and y of \(\mathcal{R}^P\):

simple Euclidean distance :

\[d^2(x,y)=\sum\nolimits_{j=1}^{p}(x_j - y_j)^2\]

normalized Euclidean distance :

\[d^2(x,y)=\sum\nolimits_{j=1}^{p}\frac{1}{s^2_j}(x_j - y_j)^2\] where \(s^2_j = \frac{1}{n}\sum\nolimits_{i=1}^{n}(x_ij-x^{-j})^2\) and \(x^{-j} = \frac{1}{n}\sum\nolimits_{i=1}^{n}x_{ij}\)

city-block or Manhattan distance:

\[d(x,y) = \sum\nolimits_{j}^{}|x_j-y_j|\]

Chebyshev or max distance :

\[d(x,y) = max_{j}|x_j-y_j|\]

In general, we use the simple Euclidean distance when all the variables have the same measurement scale

In the case of measurement scales that are too different, it is preferable to use the normalized Euclidean distance in order to give the same importance to all the variables.

6.4 How to measure the distance between classes ?

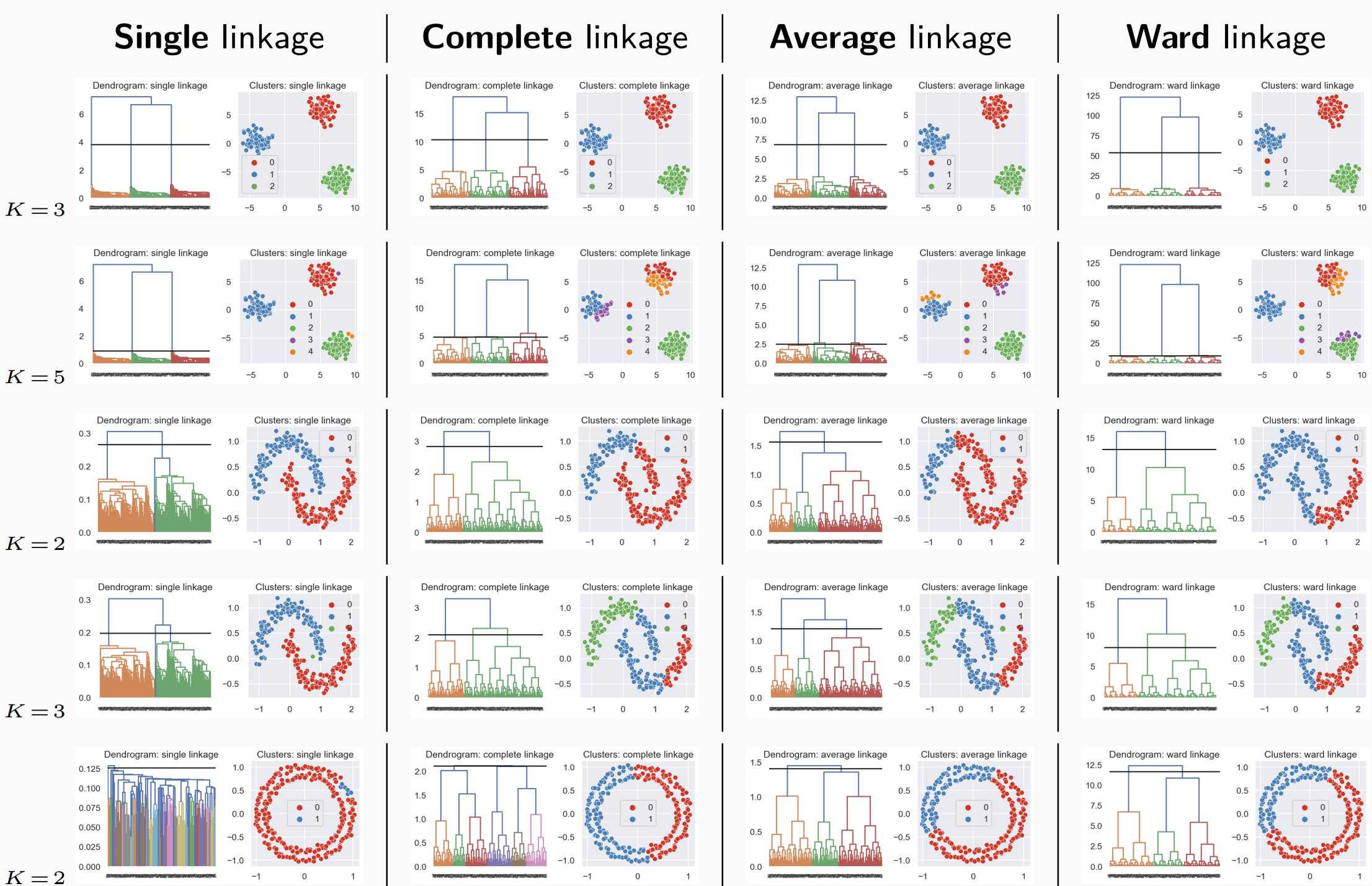

6.4.1 Linkage function

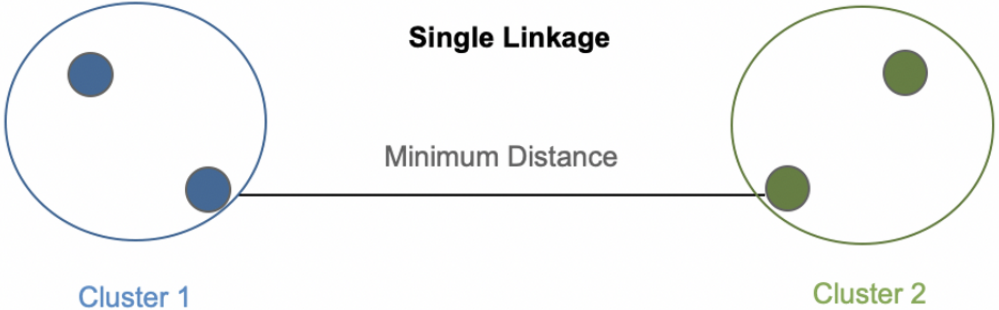

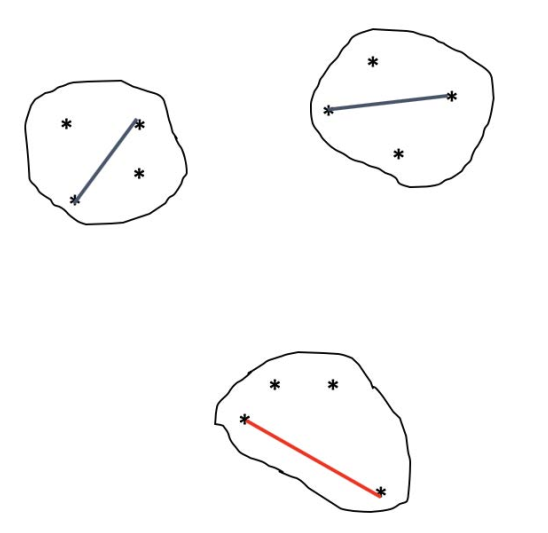

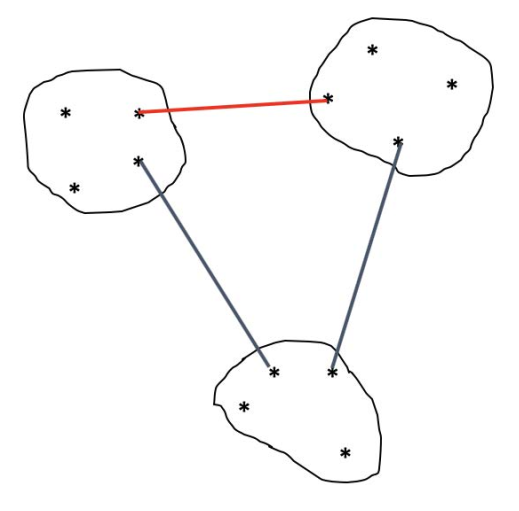

Minimum link

\[ D(C_k,C_{k'}) = \min_{x \in C_k,x' \in C_k'} d(x,x') \]

Minimal spanning tree:

Classes with very different diameters

Chaining effect: tendency to aggregate rather than create new classes

Sensitivity to noisy individuals

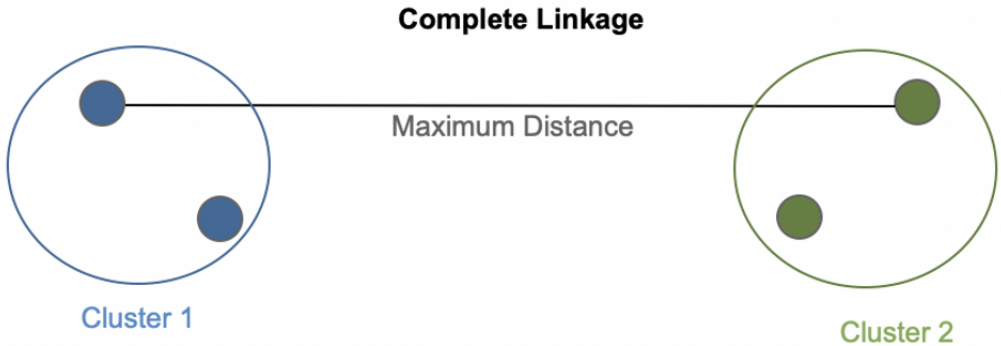

Miximal link

\[

D(C_k,C_{k'}) = \max_{x \in C_k,x' \in C_k'} d(x,x')

\]

Creates compact classes (diameter control): this fusion generates the smallest increase in diameters:

- Sensitivity to noisy individuals

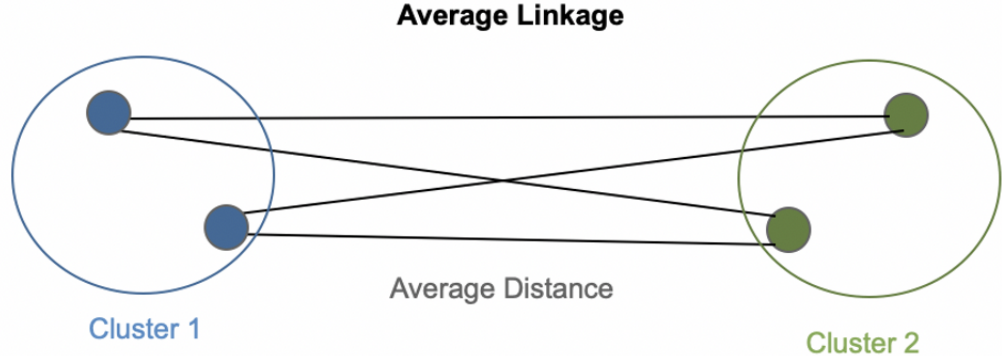

The average link

\[ D(C_k,C_{k'}) = \frac {1}{|C_k||C_{k'}|}\sum_{x \in C_k}^{}\sum_{x' \in C_{k'}}^{}d(x,x') \]

Trade-off between minimal and maximal links : good balance between class separation and class diameter diameter

Tendency to produce classes of close variance

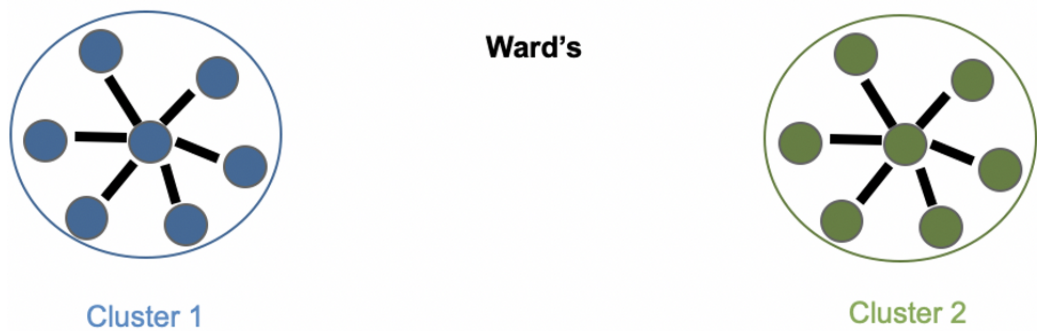

The Ward’s link

\[ D(C_k,C_{k'}) = \frac {|C_k|+|C_{k'}|}{|C_k||C_{k'}|}d(\mu_k,\mu_{k'})^2 \]

where \(\mu_k,\mu_{k'}\) are gravity centers of \(C_k,C_{k'}\)

Tendency to build classes of the same size for a given level of hierarchy.

Groups classes with close barycenters

Breaks the chain effect of the minimum link

6.5 How to evaluate the quality of a partition ?

A good partition into K classes has classes:

homogeneous : individuals in the same class are similar,

separate : individuals from two different classes are not similar.

The cohesion of the classes of a partition can be measured by the largest diameter.

The separation of the classes of a partition can be measured by the smallest minimum link.

We consider a partition \(\mathcal{P}_K = {C_1,··· ,C_K}\) in \(K\) classes. We assume here that the data are quantitative and that the weight of the individuals is \(\frac{1}{n}\).

We note \(\mu\) the center of gravity of the point cloud

\[\mu = \frac{1}{n}\sum\nolimits_{i=1}^{n} x_i\]

and for each class k, \(\mu_k\) the center of gravity of the class \(k\)

\[\mu_k = \frac{1}{|C_k|}\sum_{i \in C_k}^{} x_i, for\ all\ k \in K\]

Total inertia (independent of the partition) = total variance

\[I_{Tot} = \sum_{i = 1}^{n} d(\mu,x_i)^2 = I_{Inter} + I_{Intra}\]

Inter-class inertia = variance of the class centers

\[I_{Inter} = \sum_{k = 1}^{K} |C_k| d(\mu,\mu_k)^2\]

Intra-class inertia = variance of points in the same class

\[I_{Intra} = \sum_{k = 1}^{K}\sum_{i \in C_k}^{} d(\mu,x_i)^2\]

To obtain a good partitioning, it is therefore appropriate to both :

minimize the intra-class inertia to obtain the most homogeneous clusters possible

maximize the inter-class inertia to obtain well-differentiated subsets

Internal metric (practical situation - unknown truth):

silhouette coefficient

R-Square (RSQ) and semi-partial R-Square (SPRSQ)

External metric (specific method if we know the truth):

purity

normalized mutual information

An example of internal metric : coefficient silhouette

We assume that we have n points and K clusters. Let \(x_i\) be a data such that \(i \in C_k\).

Cohesion = average distance between \(x_i\) and the other points of \(C_k\)

\[a(i) = \frac {1}{|C_k|-1}\sum_{j \in C_k, j \neq i}d(x_i,x_j)\]

Separation = average distance between \(x_i\) and the other points of the closet classes:

\[b(i) = \min_{l \neq k }\frac {1}{|C_l|}\sum_{j \in C_l}d(x_i,x_j)\]

Coefficient silhouette:

\[s(i) = \frac{b(i)-a(i)}{max(a(i),b(i))} \in [-1,1]\]

An example of internal metric : criteria based on inertia

Let \(\mathscr{P}_K\) be a partition

- R-square:

\[ RSQ(\mathscr{P}_K) = \frac{I_{Inter}(\mathscr{P}_K)}{I_{Tot}} = 1- \frac{I_{Intra}(\mathscr{P}_K)}{I_{Tot}} \]

- Semi-partial R-square:

\[ RSQ(\mathscr{P}_K) = \frac{I_{Inter}(\mathscr{P}_K)-I_{Inter}(\mathscr{P}_{K-1})}{I_{Tot}} \]

An example of an external metric : purity

Let \(\mathscr{P}_K^{*} = \{ C_1^*,..., C_K^* \}\) be the true partition of the n points.

Consider a partition \(\mathscr{P}_K = \{ C_1,..., C_K \}\).

\[ Purity(\mathscr{P}_K) =\frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=1}^K \max_{l \in \{1,...,K^*\}} |C_l^{*} \cap C_k| \]